The stories of the proponents & translators of the English Bible still inspire, awe and shock.

In the early Middle Ages, the life of a scribe copying the Bible was tedious and uncomfortable. Scribes worked seated on the floor or on a mattress, with a board laid over their knees as a working surface. The text was either dictated or copied from a book. To avoid making mistakes, the scribes would pronounce the words aloud before writing them.

In some cases, the Bible was copied by letter instead of by word. Because some of the scribes were extremely careful, the reading scribe pronounced each letter, waited until it was repeated by the writing scribe, the scribe wrote it, and then proceeded to the next letter. This minutely detailed practice was more often done with the ancient scrolls of the Hebrew Bible.

The texts were copied onto parchment and later onto papyrus, using a stylus or quill dipped into ink. The process was indeed meticulous, but it was not dangerous. That changed as the fires of the (protestant) Reformation of the Catholic Church—in the very late Middle Ages—began to spread, consuming and martyring many whose passion was translating the Bible for the English-speaking world, a public hungry for God’s Word.

While philosopher, theologian and church reformer John Wycliffe, born around 1328, is perhaps the best-known Bible translator, his difficulties—accused of heresy and defying papal control and tried three times unsuccessfully— pale in comparison to Wycliffe’s successors who bravely defied not only the Catholic church but also the monarchs of England.

Wycliffe’s Bible, meticulously translated from the Latin Vulgate, was burned by the Catholic Church whenever discovered and Wycliffe’s bones were exhumed by the angry church, burned and scattered in the Avon. But the worst was yet to come.

William Tyndale and the Tyndale New Testament

Out of 311 priests surveyed by the bishop of Gloucester in the early 1500s, 168 priests could not repeat the Ten Commandments, only 31 knew where they came from, and 40 could not repeat the Lord’s Prayer or know who its author was. Many priests did not know any Bible verses in any language—Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French or English.

While conversing with local clergy, William Tyndale was shocked to find their ignorance of the Bible. One minister said, “We were better before without God’s law, than the Pope’s.” Tyndale replied, “I defy the Pope and all his laws, if God spare my life, ‘ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

He had a special linguistic talent and began studying languages as a young child. He could read Latin with ease at 10. At the age of 12, he entered the University of Oxford, Magdalen Hall (now Hertford College), where Foxe tells us, “By long continuance he grew and increased in the knowledge of tongues and other liberal arts.” Tyndale “was singularly addicted to the study of the Scriptures,” and Tyndale was drawn to protestant ideas.

Tyndale graduated from Oxford with his B.A. in 1512 and his M.A. in 1515 and moved to Cambridge to study the Bible and Greek. This school gave him a tremendous boost in Greek because Erasmus had taught Greek and divinity from 1511 to 1514 and the influence of Erasmus was still powerful. While there, he joined the Bible study at the White Horse Inn with Bilney, Clark, Lambert, Barnes, Frith, Ridley, and Latimer—a veritable Who’s Who of the English Reformation. He also studied the works of the reformers such as Luther, Melanchthon, and Zwingli before he left Cambridge in 1521, and soon he was preaching reformer views at Saint Austen’s Green in front of the church.

In 1521, the University of Cambridge chancellor ordered a public bonfire of all Luther’s books before the door of the Great St. Mary’s Church and the proctor and his officer spent days searching the students’ rooms, using bribery and force to get an impressive pyre. This was a signal for all secret student reformers to flee Cambridge, and Tyndale left before graduating.

Already, Tyndale had been warned and reprimanded for preaching non-Catholic reformer views by John Bell, chancellor of the diocese of Worcester, and he found refuge and served a short time as tutor and chaplain for the John Walsh family, a wealthy cloth merchant living at Little Sodbury Manor near Gloucestershire. There, Tyndale began studying Erasmus’ Greek New Testament. In it, he became even more convinced of the Scripture alone as the foundation of faith and, at this time, he translated Erasmus’ The Christian Soldier Handbook into English. About this same time, after only serving the Walsh family for a few months, Tyndale had the quarrel with a learned and respected local priest over the supremacy of the Scripture or the pope.

He decided that he did not just want to translate the Bible to formal English, but into a common English that the “plough boy” could easily grasp. He realized that “it was impossible to establish the lay people into any truth, except the Scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother tongue.”

While seeking ecclesiastical approval from the Bishop of London, because all translations had to have episcopal approval, Tyndale journeyed to London to meet with Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, who had worked with Erasmus and embraced some of the Christian Humanist ideas. But Tunstall did not believe in the Bible being in the hands of the lay people.

In May 1524, Tyndale sailed for Hamburg, never to see England again, going next to Wittenberg, Germany, the most favorable city in Europe to reformer views. While there, he had several meetings with Martin Luther and met a former friar, William Roy, who helped Tyndale finish translating the New Testament in 1525 in just over a year.

Finding a printer was a difficult task, but he found one in Cologne. One assistant spoke too freely over wine and soon English spies came to raid the printing. Just moments before they arrived, Tyndale escaped with the printed sheets. This edition was the first English Bible translated from Hebrew and Greek, it used the Received Text and it was soon completed in Worms, a free imperial city then in the process of adopting Lutheran views. It was printed in December 1525. Although 6,000 New Testaments were printed and smuggled to England in bales of cloth and barrels of wheat, the fires of persecution burned so many copies that only three copies of that first edition survive today and only one complete copy.

The moment that translation was smuggled into England, it caused a sensation. King Henry VIII ordered it to be burned, yet hundreds were reading it and were willing to go to prison to distribute the Bible.

Tyndale learned eight or nine languages over the years, including French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish, English and probably Dutch, and he was so fluent with many additional dialects, that when someone met him, they could not tell which was his mother tongue. Tyndale also used multiple aliases and moved many times, always in hiding from the Catholic authorities, so it is sometimes difficult to know where he was in Europe.

Tyndale retreated into hiding in Hamburg in January 1530, and by using his extraordinary memory, speed, and accuracy of translation, his Pentateuch was ready to be published and he went to Antwerp for printing. Work on the Old Testament progressed and Tyndale probably finished the books of Joshua through the Chronicles and Jonah, which were left in the capable hands of John Rogers (who later published them in the Matthew’s Bible).

However, King Henry VIII had earlier made it illegal to publish the Bible in English, and Tyndale was betrayed by a friend named Henry Phillips in 1535, who was in the pay of Thomas More working with Bishop Stokesley. As a result, Tyndale was imprisoned at Vilvorde Castle, near Brussels, charged with teaching justification by faith.

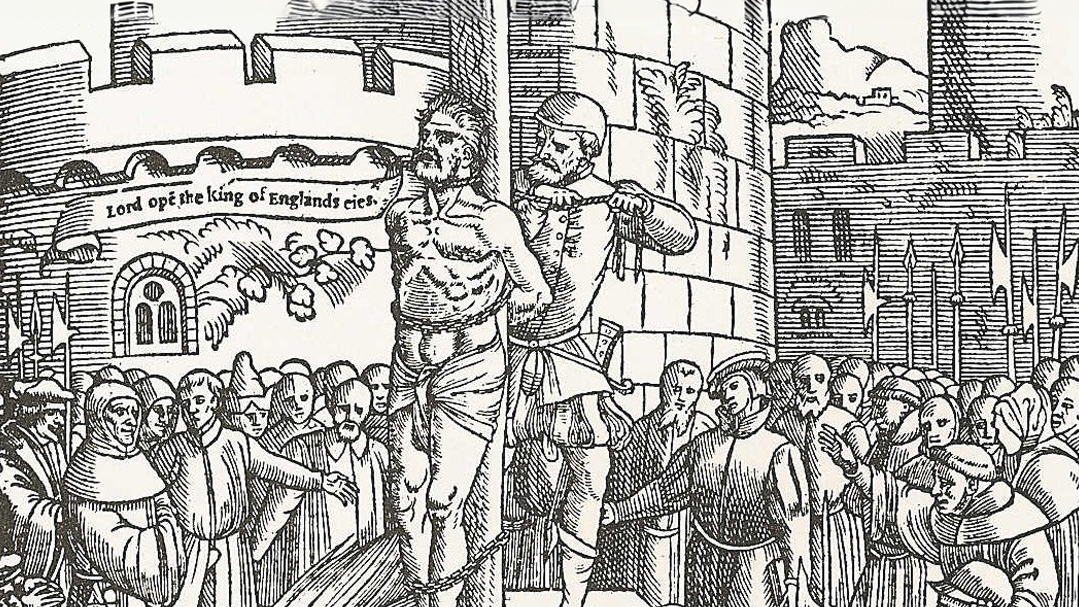

Although Thomas Cromwell tried to intercede on his behalf, over a year after his trial, Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake. Just before death, Tyndale shouted, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

God answered Tyndale’s prayer and in just four years, the king authorized the publishing of the Great Bible to be placed in every church in England (a Bible that was virtually Tyndale’s Bible largely unchanged). Today, over 90 percent of the magnificent Authorized King James Version retains the text of William Tyndale.

Tyndale’s courageous struggle to get the Scriptures in the hands of the common man of England, not only spread the flames of the Gospel, but also inspired other men to translate and publish the Bible.

Tyndale’s Bibles were banned by royal proclamation in 1530 and Henry VIII promised to authorize an English Bible prepared by learned and Catholic scholars. Thomas Cromwell seized upon this opportunity and tried to get several people to work on the translation but he was not successful.

Miles Coverdale

Miles Coverdale was an English reformer, Bible translator and Bishop of Exeter (1551-1553). Born about 1488 in Yorkshire, Coverdale studied philosophy and theology at Cambridge and graduated with a bachelor’s of canon law in 1513 and was ordained a priest in 1514 at Norwich.

He entered the House of Augustinian friars in Cambridge where Robert Barnes returned to become the prior after studying under Erasmus and developing humanist thought. At Cambridge about 1520, Barnes read aloud translations of Paul’s epistles and writings of classical authors.

Coverdale had earlier been carried away by the preaching of the Gospel under Thomas Bilney and Hugh Latimer. This sparked a fire in him. He was not only inspired by the Gospel, but he also became interested in the Reformation. After the passage of the Six Articles (confirming Catholic doctrine) by Parliament, Barnes was put on trial for preaching Lutheran views, and Coverdale acted as his secretary and defense. Barnes was made to carry a bundle of sticks (weighing up to 120 pounds) to St. Paul’s cross and in 1540, he was burned at the stake at Smithfield with two other reformers.

After seeing the wrongful treatment of his friend, Coverdale said that he determined to be fully dedicated to God and from that moment, “he gave himself wholly to spread the truth of the Gospel.” In Antwerp, Coverdale met Tyndale and was soon helping him with Bible translation. After Tyndale was betrayed, arrested, and killed, Coverdale continued the work alone to produce the first complete English Bible in print.

Because the 1534 Canterbury Convocation petitioned Henry VIII for the whole Bible to be translated into English, Coverdale dedicated the Bible to the king, hoping for his acceptance. The Coverdale Bible would influence virtually every English Bible to follow.

Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury

There was an attempt to return England to being a full Catholic country and in 1553, Queen Mary, Henry VIII’s daughter, began a stern reign with an immediate return of all Catholic vestments, images and practices and a suppression of the English Bible, Gospel preaching and all protestant books. Previously in England, since the time of Wycliffe, about 160 people had been burned at the stake during the previous 200 years.

All of Continental Europe enforced burning for heresy, or not agreeing with Catholic doctrine, and in Europe about 20,000 people were killed during the 1500s, including burning 350 Anabaptist preachers at one time in front of the Catholic Church of Heidelberg, Germany. But during her five-year reign, the English queen was estimated to have burned at the stake over 300 evangelical Christian believers, including over 50 women. Fittingly, she was known as “Bloody Mary.”

Soon, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury was called into question. He had quietly tried to maneuver the country toward a more protestant concept, and his 1549 Prayer Book was a clear move to include the Gospel and fewer Catholic concepts. He had helped Henry VIII in his attempt at divorce and rose to prominence, but his obvious belief in the Gospel had put him in conflict with the Catholic Church.

A frail man with a weak emotional spirit who greatly feared dying, under pressure he recanted and signed seven documents that denied faith in the Bible alone and affirmed Catholic teaching. But his conscience soon bothered him. Knowing that he was an old man and would die soon, he realized that he could not face God with this on his conscience, so he recanted his recantation! He wanted to affirm his faith in the Bible and deny Catholic teaching.

At the Mary Magdalene Church of Oxford (now known as the Martyr’s Church), Cranmer was asked to preach. Knowing that protestant and Anabaptist preachers were being killed almost daily (five Anabaptists were burned that same day) and that all English Bibles were being burned, he decided to publicly admit that he actually believed in the Bible as his sole authority, and in God, not the pope or the queen, as his final judge. As soon as he finished his sermon, he started to run out of the church and was nearing the outer courtyard when the officers caught him.

Taken back to the same church where he had just preached, he was put on trial and quickly condemned to death by burning. When they chained him to the stake, he asked that his arms be left free. As the flames reached near waist-high, he raised his right hand high and said three times, “This hand hath offended God!” and then put it into the fire. This hand had signed the documents denying biblical faith and promoting Catholic teaching.

Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were also subsequently burned for their faith, and together with Thomas Cranmer, are called the Oxford Martyrs, belittled and remembered with the children’s song, “Three Blind Mice.”

Thomas Bilney

Born about 1495 in Norwich, Thomas Bilney was a short man of plain looks and known as Little Bilney. He graduated from Cambridge with a law degree and became a priest but was burdened by his guilt of sin. Searching to find peace, he finally decided to do something desperate. Going to Oxford’s Blackwell bookstore at midnight, entering covertly through the back door, he bought an illegal book, the 1516 Erasmus Greek New Testament.

Thinking that he was too sinful to be saved, he read it until he saw Paul’s words in 1 Timothy 1:15 which said, “This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the chief.” Realizing that the Apostle Paul was calling himself the chief sinner, that if God could save and free Paul from sin, then God could save and free him too, and Bilney called upon God to save him.

Following his obtaining a license to preach in 1525, Bilney preached in the diocese of Ely, but was soon called and warned to not preach the doctrines of Martin Luther. Within the year, Bilney was dragged from the pulpit while preaching at St. George’s Chapel Ipswich, arrested and imprisoned at the Tower of London, tried and convicted of heresy, and eventually forced to recant.

After being kept in prison for a year, he was released in 1529, but he had remorse for recanting and believed that he had committed apostasy. So, he determined to preach the truth of the Gospel again and began to preach in the streets and fields until he reached Norwich, where he was arrested and condemned to be burned.

While waiting in prison to be burned at the stake, a concerned friend, Matthew Parker, came and said, “Bilney, can you endure the pain of burning alive? Can you take the fire?” Bilney put his index finger in the flame of a candle nearby and let it burn all the way to the exposed bone and showed it to his friend saying, “Yes, I can take the fire,” and he quoted Isaiah 43:2, “When thou walkest through the fire, thou shall not be burned.”

He was burned at the stake at the Lollard’s Pit, Norwich, in August 1531.

Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley

Hugh Latimer was born in 1487 and graduated from Cambridge with a bachelor of divinity in 1524, writing a disputation against the reformation doctrine, especially the work of Philip Melanchthon, the colleague of Martin Luther. Latimer described himself as a fierce Catholic, and as “obstinate a papist as any was in England.”

But Latimer was saved while hearing the confession of Thomas Bilney, and he joined the reformers in the Bible study at the White Horse Inn begun by Bilney, promoted the translation of the Bible into English, and began to publicly preach evangelical doctrine.

Warned to not preach anti-Catholic doctrine by Cardinal Wolsey, he continued this preaching in other churches and later opposed the Six Articles (the reintroduction of Catholic teaching) under Queen Mary. Tried at Oxford, he argued against the Catholic teaching of the real presence of Christ in the Mass, as well as the saving merit of the Mass, knowing we are only saved by grace through faith in the blood of Jesus. He also looked for the soon return of Jesus, and said, “It may come in my days, old as I am, or in my children’s days, the saints shall be taken up to meet Christ in the air, and so shall come down with him again (1 Thessalonians 4).”

When Ridley and Latimer were being tied to the stake to be burned, Ridley was worried but Latimer said, “Be of good comfort, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s Grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”

Today, there is a painted X in front of the Oxford Blackwell bookstore where Ridley and Latimer died and nearby is an elaborate Gothic monument to the three Oxford martyrs.

After Edward VI died and Mary Tudor came to power, all reformer ministers were called to appear before the Privy Council. Miles Coverdale was placed under house arrest in Exeter, yet through intervention of his brother-in-law, the chaplain to King Christian III of Denmark-Norway, he was able to leave with his wife, finally settling in Geneva where he next assisted with the translation of the Geneva Bible.

Even though it was a decisive period of persecution during the English Reformation, there was a great outpouring of God’s Spirit in England through the preaching of men like Latimer, Ridley, Bilney and Cranmer, and there were Bible studies among the royalty and aristocracy resulting in a great spiritual revival with a large number of the masses saved when people could hear and read the Bible.

Realizing the Only Truth was the Bible

Often, during these times, men heard the Gospel and were saved, and yet paid the ultimate price to have the Bible in their language and to share that Gospel with the unsaved. They realized the truth of the gospel for salvation and that the Bible was the only true Word of God to men and the supreme need of mankind—and it needed to be in the hands of the common man, as well as the crown and church leaders.

Sacrifices also were being made in Europe as people learned the Gospel and promoted the Bible. Balthasar Hubmaier, a German Anabaptist leader and Reformer was another faithful man publicly martyred.

As he was taken to be burned at the stake, he preached a sermon to the onlookers and many people were saved. Then, as the people came to light the fire by burning sermons and the Bible, Hubmaier said:

“You may burn me for my faith and you may burn the Bible, but Truth is Immortal and the Word of our God shall stand forever!”

No matter how much the Bible and its preachers and translators suffered, the King of Books still stands today!

This is the great price paid for the Gospel and for the Bible to be in the language of the people. Unlike these men, today, we live in a free country and can easily find a Bible.

Let us commit our lives to telling someone about Jesus, to stand for the Bible and be willing to go if God calls us to other lands to win the lost and let the world know the truth of the King of Books, a right for which these men fought with all their heart, body and soul.

King of Books by Dr. Lonnie Shipman

The Bible is the world’s most amazing book that can speak the words of God directly to the hearts of those who hear or read it. While our current generation often doubts the Bible and the supernatural working of God, the truth of the Bible is evidenced in archaeology and preserved in Bible manuscript history.

The King James Bible is truly the King of Books, the king of all books ever written. It has influenced the morals, the government, the worldview, the culture, the language and literature of the nations, as well as the growth of churches and spiritual lives of people.

Dr. Shipman “has skillfully taken complex issues in archaeology and manuscript evidence for the Bible and made them accessible to the reader. This book will excite the reader about what God has done and is about to do through the Word of God!”—Lifeway President Emeritus Dr. Jimmy Draper

Dr. Lonnie Shipman

Lonnie Shipman graduated from Arlington Baptist University with a BS, Dallas Baptist University with a BM, Baptist Christian College (BA), Louisiana Baptist University (MA), Baptist College of Florida (MM), Louisiana Baptist Theological Seminary (Mdiv, ThD) and Pacific International University (DSM).

He has done graduate work at Pensacola Christian College, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and a special research study at Christ Church College of Oxford University, England.

“God’s Word” is a Spiritual Book; composed by a Spiritual Being; for spiritual beings.

Truly inspiring. So blessed and encouraged reading g this article. Thank you very much

Paul

As a history buff, especially The Bible which is so taken for granted in America, I desire deeper knowledge of any history about The Book…my family was part of the persecuted anabaptist I’m told and blood spilled for our freedom is worthy our seeking